Zf620. Josefina “Joey” Guerrero: The Leper Spy of the Philippines. A book has been written about her and it is available on Amazon and perhaps at other venues.

—————————————–

There is so much to learn about the people who experienced WWII. It is a passion of mine to learn more. I never heard about this spy, this person, until a good friend of mine, a Filipino Flag Officer and graduate of the AMA West Point, sent me an email about her and said this:

Hi Karl

You might find this World War II story interesting. I did a copy-and-paste of a subscription article.

Imagine — the first FOREIGN LEPER allowed entering the USA!

Ray

And I learned a lot in the www about this Filipina Lady.

——————————————————–

Zf621. Josefina “Joey” Guerrero, from Outcast to Spy to Outcast: The War Hero with Hansen’s Disease. This is a National WWII Museum at New Orleans image.

Diagnosed with Hansen’s disease and unable to access medication in Japanese-occupied Philippines, Josefina Guerrero decided to join the guerrilla movement and become a spy. Her disease allowed her to move untouched by the Japanese, providing critical Intel to American forces as they moved towards the Battle of Manila.

The best coverage about this WWII story and person, I believe, is this WWII National WWII Museum at New Orleans story by Lea Schram von Haupt. I copied the above picture and the 3 pictures below along with the texts. This is the URL of her article, click here.

Zf622. Josefina “Joey” Guerrero, one of her outstanding feats as a guerrilla. This is a National WWII Museum at New Orleans image.

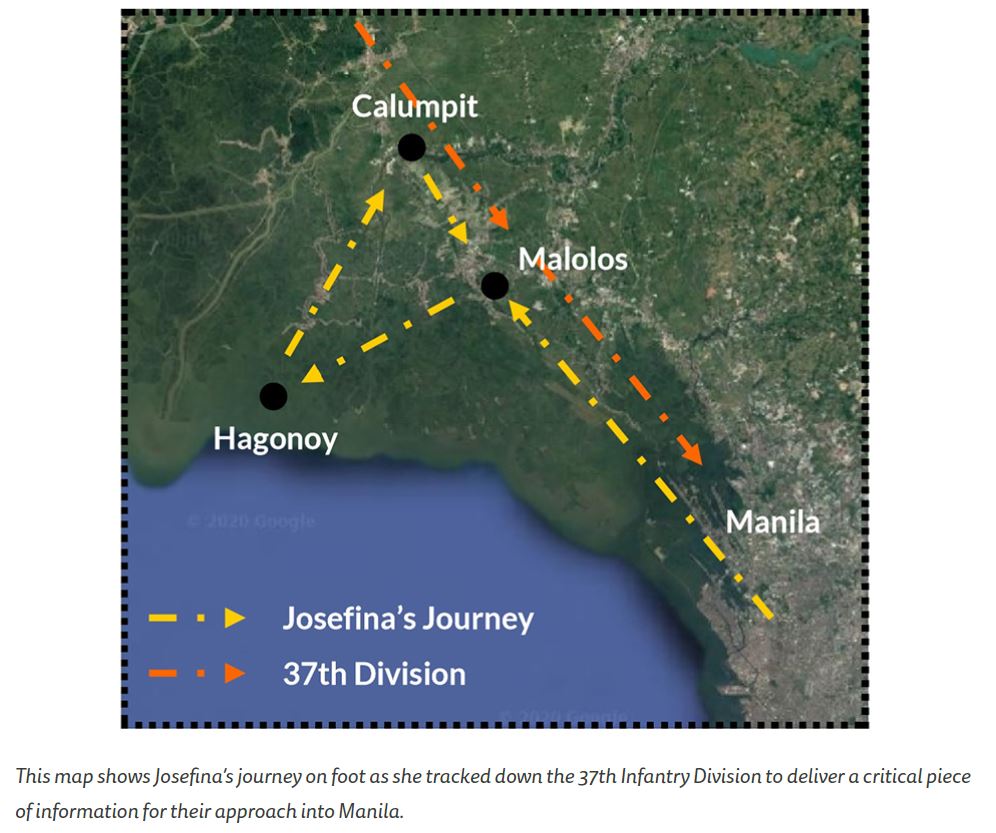

Despite her paralyzing headaches and fatigue, she taped the map to her back and set off on foot. She walked 25 miles to the town of Malolos. Here, she took a boat around an active combat zone through the town of Hagonoy, outrunning river pirates. Back on land, she walked the remaining eight miles to her destination: Calumpit. Guerrero arrived only to discover that just three hours earlier, the American troops had already advanced to Malolos. She began walking once again, back to Malolos and eventually placed the map in the hands of Captain Blair of the 37th Infantry Division.

Zf623. The Tala Leprosarium in Novaliches, 15 miles north of Manila, where Josefina “Joey” Guerrero was admitted to. This is a National WWII Museum at New Orleans image.

After the war ended, Guerrero’s disease made her an outcast once again. She was exiled to a leprosarium 15 miles northeast of Manila. The conditions were deplorable. Only four nurses tended to 650 patients. There were only 10 buildings on the grounds with a maximum capacity of 300 patients, and there was no running water or electricity. Most of the patients slept on the ground in unclean conditions. Every year, dozens of patients died from malnutrition.

Guerrero set about cleaning the camp as much as she could, and became a teacher at the colony and built coffins for the deceased. She wrote a letter to a friend of a friend in San Francisco, describing the conditions of the leprosarium. Her letter found its way to the Catholic Chaplain at the National Leprosarium of the United States in Carville, Louisiana. As her letter was passed around, it caught the attention of the Manila Times. An above-the-fold exposé was written on the conditions at the colony. Other news sources caught on to the story and wrote their own pieces. Finally, the government sent investigators to the leprosarium and confirmed the conditions. New dormitories were built and the leprosarium received beds for both the dormitories and hospitals, so that all patients had somewhere to sleep. Food rations were improved, telephone service was installed for emergencies, and water stations were built. The campus was cleaned up and medical staff added.

Zf624. The Carville Leprosarium, where Josefina “Joey” Guerrero was admitted to and healed. This is a National WWII Museum at New Orleans image.

After hearing about the community at Carville, Louisiana and the medical breakthroughs being made in the United States, Guerrero felt hope about her condition for the first time. She fought to obtain the first American visa for a foreign national with Hansen’s disease. In 1948, Guerrero arrived in Carville. She was diagnosed with an “advanced” case and it took nine years of treatment to put her disease into arrest. She continued to fight publicly against the maltreatment and discrimination of people with Hansen’s disease. Over the years, she prepared herself for freedom from the walls of the leprosarium. Finally, in April of 1957, she was discharged from Carville.