Zf841. Telesforo Trinidad was born on the island of Panay, entered the U.S. Navy Insular Force in 1910, and served through two world wars retiring in 1945. The USS San Diego (ACR-6) also served as command ship of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

================================================

Zf829

The United States Navy and a Philippine Heritage

An Essay on Friendship by

Rear Admiral Daniel W. McKinnon, Jr. SC USN ret.

Copywrite 2021

The author gave me permission to post this essay. He and others have a special place in my heart.

I believe that the author and a few shipmates of his where the key people in convincing Congress to accept responsibility the Veterans Cemetery in the Clark Economy Zone.

They were also the key people in getting agreements between all the organizations involved in the return of the Balangiga Bells and another bell in the La Union Province.

See his biography at the end of this essay!

==================================================

It was 1957 when I reported as an Assistant Supply Officer on board the USS Boxer (CVS-21) and later assigned as S-5 Division Officer and Wardroom Mess Caterer. Racial segregation in the Navy had officially ended less than a decade earlier due do orders from President Truman. Our stewards were African-American, Philippine-American, or “Philippine-Nationals”. Stewards lived forward under officer’s country in two berthing compartments on the starboard and port sides of the ship. Unlike sailors in other divisions who used trough urinals, team bathing, and stood in line for a shave, steward compartments had their own showers, toilets, face bowls, and lockers. The Essex class aircraft carrier had been built in World War II and my men were living a unique legacy; segregation as a feature of naval architecture. Private berthing compartments; one for Filipinos and one for African-Americans.

Philippine “nationals” serving in the Navy was a mystery. During the next 35 years I would come to discover the history of a unique partnership. This essay is the story of the Philippine heritage in the United States Navy, and my journey, appreciation, and personal debt to those with whom I served.

The history of the Philippines is remarkably intertwined with the United States. It was for half a century our colony. Its school system and governance are in our model. Along with Canada and Great Britain it is arguably our nation’s closest ally of the past century. It is the third largest English-speaking nation in the world and over 300,000 Americans live in the Philippines and four million former Filipinos live in the United States where “Filipino” or Tagalog is the fourth most spoken language.

Zf830. Popular World War Two poster published at a time when Americans and Filipinos were pushing Japanese forces out of their country. Earlier, after the fall of Bataan in April 1942, the infamous Bataan Death March across Luzon to Camp O’Donnell saw over 500 American deaths by abuse and wanton killing, while well over 5,000 Filipinos experienced the same fate. Brothers in blood then. Friends and comrades forever.

The history of the creation of the Philippine nation is well told. How the Spanish American War was intended to help the Cuban “War of Independence” against a European power. How the United States sent the Battleship Maine to the Havana Harbor to ensure the safety of Americans. How on February, 15, 1898 the Maine sank following a massive explosion with 266 men killed and a Spanish torpedo blamed. How a rallying cry “Remember the Maine” helped pave a road to war. How our blockade of Cuba led Spain to declare war on April 21, 1898. How Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt stepped down and became Teddy Roosevelt of the “Rough Riders”, and as Acting Navy Secretary had ordered the U.S. Asiatic Squadron to Hong Kong. How Commodore Dewey, far from our shores across the Pacific Ocean, defeated the Spanish fleet in the “Battle of Manila Bay” and became our first, “Admiral of the Navy”. Then came the acquisition of a colony from Spain on the other side of the world for twenty million dollars, a national debate on imperialism, the Philippine-American War, “Benevolent Assimilation”, colonialization, a commonwealth, and a World War that saw the devastation of the city of Manila, “Pearl of the Orient”, second only to the destruction of Warsaw.

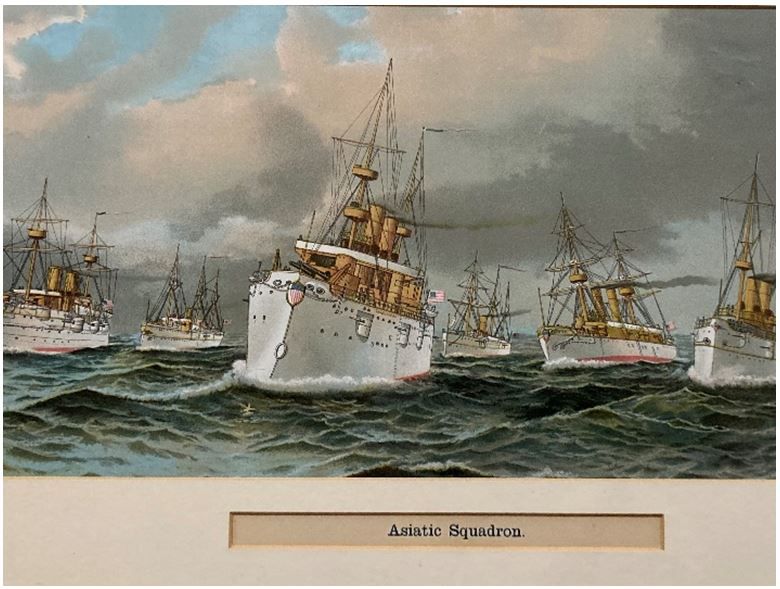

Zf831. In 1898, Acting Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt ordered the. Asiatic Squadron to sail to Hong Kong and prepare for a war with Spain. Soon the Cruiser USFS Olympia (C-6) with Commodore Dewey and his ships were about to make Philippine American history. (Chromolithograph, “Asiatic Squadron”, writers’ collection.)

On the 4th July 1946, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander of the U.S. Army Forces, Far East (USAFFE), in front of the internationally famous Manila Hotel, declared the Republic of the Philippines a free nation. In 1935 it had become a self-governing commonwealth. Joining MacArthur, the Philippines first President of the independent Third Philippine Republic, Manuel Acuna Roxas, declared, “We have reached the summit of the mighty mountain of independence.” Today the Philippines celebrates its independence on 12 June, the date in 1898 when Emilio Aguinaldo declared the island nation free from Spain. The Manila Hotel sat across the park from the famous Army Navy Club, parent of the Army Navy Club of Washington D.C., and birthplace of the Military Order of the Carabao. The Order of the Carabao honoring the humble beast of burden of the Philippines, the Carabao, was organized in reaction to the less than humble wearing of a jeweled emblem of the haughty Order of the Dragon. The Order of the Dragon, which has passed into history, was organized by soldiers of the China Relief Expedition that had fought in the Boxer Rebellon. The Military Order of the Carabao, that began as satire in the Philippines, has lasted with an honored tradition, the Carabao Wallow held annually with national dignitaries in Washington D.C.

Filipinos humorously describe their history as, “Three hundred years in a convent and fifty years in Hollywood”.

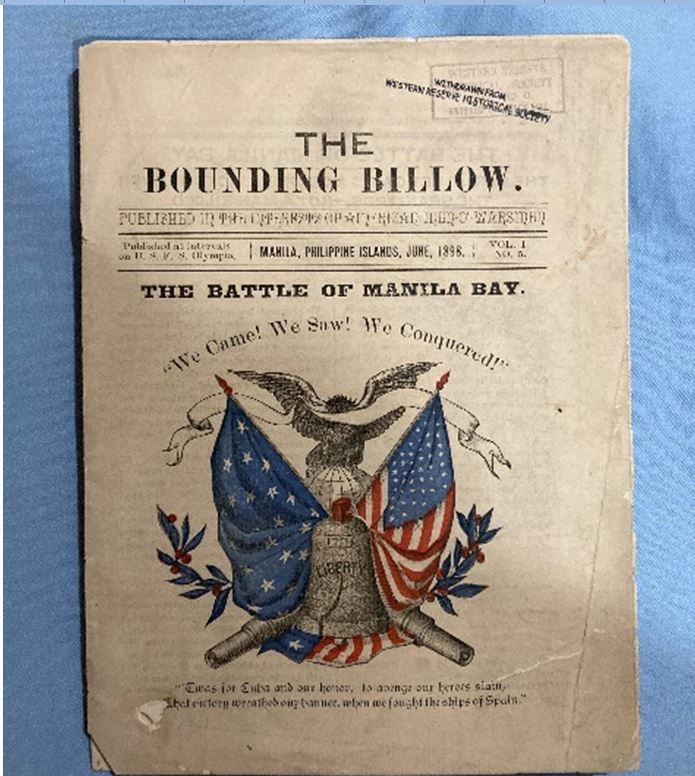

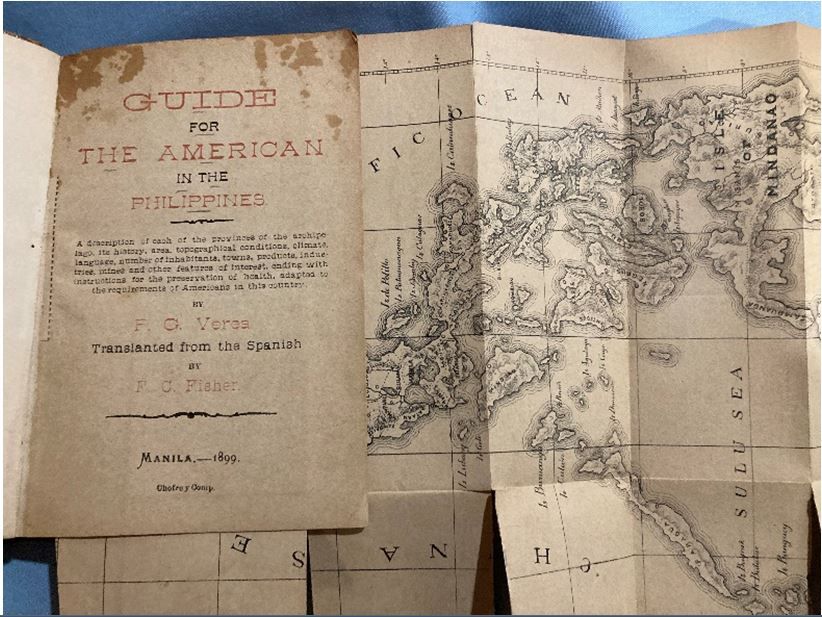

Zf832 & Zf833. The Battle of Manila Bay took place on the first of May, 1898, and the U.S.F.S. Olympia printed the first detailed description of the battle in the ship’s newspaper, “The Bounding Billow”. Lacking paper, they “borrowed” a bundle from the Spanish on Cavite. As American troops began to arrive, “The Guide for Americans in the Philippines” was published with detailed maps and a beautiful geography and description of the archipelago translated from the Spanish. (Writer’s collection.)

in 1901 President McKinley signed an Executive Order allowing the Navy to enlist 500 Filipinos. But Filipinos had been at sea in the Americas centuries before when the ships of “New Spain”, that included the Philippine Islands, crisscrossed the Pacific via the “Manila Galleon Trade”. Some sailors jumped ship, settled in Louisiana in the 18th century, and established the community of St. Malo. A century later Filipinos were fighting in the Battle of New Orleans as “Manilamen”, and Philippine-Americans were on both sides in the Civil War. Filipinos are credited with being the first Asians in California having arrived on a Manila Galleon in Moro Bay in 1587.

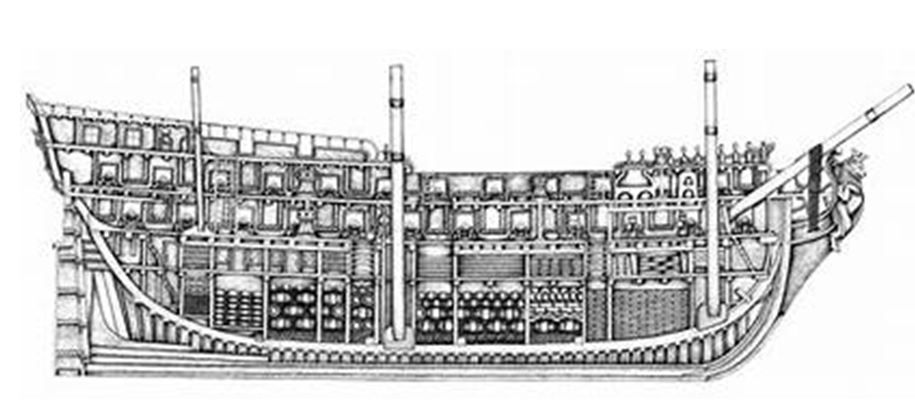

As a boy I loved movies of the famous “Spanish Galleons”. Three masted wooden warships at sea with their cannon, swords, heroes, and sometimes pirates. Who would have known that many were actually built in the Philippines and sailed as “Manila Galleons”? Hulls were stronger and built with wood that did not easily splinter under cannon shot. Ships became larger, took about 2,000 trees to provide the timber, and constructed in six months compared to two years in Europe. The islanders were known for their woodworking skills, and today one might mistake a Philippine religious wooden Santos for an antique from Mexico.

Zf834. A 1655 etching of Manila galleons in the harbor of Acapulco.

For over 200 years, Manila Galleons crossed the Pacific to Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico. Mexican silver would be used for trade in Manila and galleons would meet Chinese traders at the entrance of a great bay. Chinese merchants, or “Xiang-li”, conducted trade on a point of land protruding into the almost landlocked Bay of Manila. They could not enter the city of Manila. The riches of Asia, spices, porcelain, elaborate fabrics, even Persian carpets, would return by galleon to Acapulco and then by donkey caravan across Mexico and again by sea on to Spain.

Zf835. For hundreds of voyages, Manila galleons crossed the Pacific in ships cramped with cargo and crew. No wardroom. No stewards. No gedunk.

Many U.S. Navy and Marine Corps officers saw duty with commands at the old Spanish base at Cavite whose history included the galleon building shipyard, fort, hospital, graveyard and famous arsenal. The peninsula used by the “Xiang-li” became Naval Station/Naval Air Station, Sangley Point. Since defeat of the Spanish fleet by Dewey took place just off shore, some call the victory, the “Battle of Cavite”. Defeat of American forces by Japan at Cavite in 1942 saw the capture and of many Americans, including Vice Admiral Ken Wheeler, with whom I served. Ken was imprisoned in a slave labor camp on Davao, and later saw his closest friend, Bill Elliott, whom he pulled ashore in Olongapo from the sinking hell-ship Oryoku Maru, shot because he was too weak to be of value in the slave labor camps of Japan.

Filipinos entering the U.S. Navy as members of the “Insular Force” in 1901 was only the beginning. They could bring their Philippine families and until the end of WW I could enter several ratings. After the war, Filipinos joining the Navy meant becoming mess attendants and stewards, slowly replacing Chinese and Chamorros (Guamanians) over the next twenty years. In 1947, under an agreement with the new Republic of the Philippines, its citizens could be recruited into the Navy. In 1952 the annual quota was increased to 1,000, and then later to 2,000, to meet a need for more stewards as Blacks began moving out to other ratings.

Laws on a path to citizenship became complex over the next few years, but service in the Navy was generally counted on as a means of becoming an American citizen.

Fifty years ago, Admiral Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt became Chief of Naval Operations and brought more change. Filipinos could be recruited for Seaman Recruit instead of Stewardsman, and most ratings became open. The famous Z-gram author also made sure that Navy commissaries offered food popular with Filipinos and other nationalities. As “foreign nationals”, Filipinos could not enter ratings requiring access to classified information. That is why you saw many Filipinos with careers that began in the medical, clerical, and supply ratings.

Zf836. A 1655 etching of Manila Bay with a depiction of Subic Bay to the north. You can see the island of Corregidor, and also Grande Island at the entrance to Subic Bay. Shown are Manila galleons and “junks”, or in Spanish “junco”, the Chinese trading ships of the Xiang-li.

I became Commanding Officer, Naval Supply Depot (NSD), Subic Bay, Philippines in 1980, with responsibilities for support of both U.S. Navy and Marine Corps forces in Asia and the Indian Ocean. NSD Subic held Pacific area war reserves and provided the Seventh Fleet and USMC units supplies and re-supplies, petroleum, cash, food, fuel and even aviation fuel to the U.S. Air Force. We had USMC and USAF detachments; assignments in their services that were so attractive we rarely lost a soft ball game. It was a joint team. The biggest asset was a loyal Philippine workforce of 2,000 professionals skilled in every facet of logistics; from driving forklifts to designing computer programs; from keeping accounting records to loading aircraft and ships; from pumping ship fuel to buying ship repair. The 200 person staff of our computer department were so professional we were a recruiting source for Philippine business and banks. Recruiting new sailors for the Navy was on-going in the country, but the waiting list for testing and interviews had thousands of applicants. An annual public notice was not issued. Recruitment of Filipinos continued until 1992 when the Military Bases Agreement failed Philippine Senate ratification the year before. For those of a certain age, this ended a beautiful time in history.

Zf837. Early photo of Filipinos at sea in a pre-WW I unidentified ship.

The U.S. Navy lost its principal logistics and support hub in Asia. Today we observe the debate on how best to support deployed naval forces far from home, operating in a part of the world where diplomatic and military moves take place daily in the chess game of international competition. In Subic Bay and the modern city of Olongapo, we see a “free port”, and a thriving international commercial trading and tourist center.

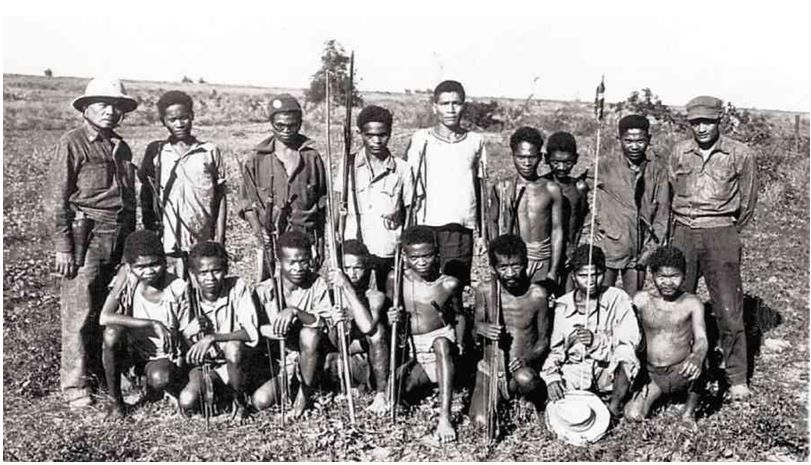

Those of us who remember the Subic Navy base and liberty on Luzon and the nearby city of Olongapo, may also remember the “Aeta”. They, too, have a long history with the U.S. Navy. The Spanish called them, “Negritos”. We did too. The “Aeta” are a small native people you would find on both the Subic Naval base and Clark Air Force base providing security. One of over 70 indigenous peoples of the 7,000-island archipelago, they arrived on the island of Luzon over 35,000 years ago. The Ayta Magbukun community has the highest known level of Denisovan ancestry in the world. Easily, the Aeta can be considered the first peoples of the Philippines.

Zf838. The Aetas of WWII Squadron 30 of the Luzon Guerrilla Forces (LGF), Southern Tarlac Military District under Capt. Bruce. Among those saved was Lt. Alex Vraciu. The Aeta and American Navy partnership began in 1905 with establishment of a Naval Station at Olongapo on Subic Bay.

Sailors may remember buying their famous knives as souvenirs on the way to liberty in Olongapo. Ships remember the Aeta going through trash looking for accidently discarded classified correspondence. They could not read English, but they could recognize and return any piece of paper marked “Confidential”, “Secret”, or “Top Secret”. Naval aviators remember them teaching survival skills at the Jungle Environmental Survival Training center (JEST) on Cubi Point. Tourists today can learn the same skills as well as how to live within the beauty of nature and protect our environment. Veterans of WWII may remember them for saving downed pilots in the mountains of Luzon, or pulling Bataan Death March prisoners into the brush. A Philippine charity, the “Subic Indigenous Peoples Assistance Group” (SIPAG) is assisting the Aeta develop a livelihood center on the former U. S. Naval Magazine as they attempt to maintain their original way of life on tribal lands now set aside by the Philippine government. The Project Handclasp Foundation (PHF) provided a “Tevelson Grant” of $80,000 for the “Handclasp Aeta Partnership” to assist in establishing the center. The Aeta story is special. It will hopefully be told in a Philippine documentary, “A Forgotten Friendship, America’s 100 Year Relationship with the Aeta”.

Zf839. Bataan Death March starting point marker used to note the April 1942 journey from Mariveles to Camp O’Donnell on the island of Luzon. The Aeta helped POWs slip away.

The Navy’s Project Handclasp (PH) lapsed a few years ago. Many Sailors and officers will remember bringing boxes on board ship of donated goods from private industry or charities; toys, school supplies, medical material, and family health articles. Donated skate boards became village transport, and feminine hygiene pads became soccer knee pads. Donations would be distributed ashore by Sailors and Marines on Community Relations (COMREL) excursions outside the United States. The U.S. Naval Supply Depot (NSD) Subic had a large inventory of PH material, as did supply activities in San Diego, Jacksonville, Singapore, and Sigonella. It would not be unusual to find NSD Subic families, American and Philippine, in a provincial town on a Saturday, painting a school, donating books, or distributing toys. The inventory was owned by the Project Handclasp Foundation, with a board composed of retired Navy officers and senior civilians. We decided that our remaining assets would go to charitable projects in the Philippines. All had served or been there often. We would make “Tevelson Grants, or Donations”, in honor of the Navy’s long time program director, Commander Charles (Charlie) Tevelson, without whom it can be arguably, and accurately, stated the program would not have existed.

The first donation was over 130 pallets of water purification kits and treadle sewing machines that did not require electricity. It was to the Philippine Red Cross whose chairman is Richard J. (Dick) Gordon, Mayor of Olongapo in the 1980s, and friend to many U. S. Navy officers. In 1980 he and I co-founded the Subic Bay Industrialization Opportunities Foundation to provide training and employment for the youth of Olongapo. In 1981, then Vice Admiral Carl Trost, Seventh Fleet Commander, lifted a curfew on Olongapo after Mayor Gordon’s successful campaign of safety and cleanliness. Years later, retired CNO Carl Trost, as the Grand Paramount Caribou, at his friend’s Dick Gordon’s request, had some of the more raucous and racist language removed from the Military Order of the Caribou song book; songs of yore sang with gusto and goodwill at the annual Carabao Wallow in Washington D.C.

The second donation was $150,000 to create the Children of Marawi Project, which with the assistance of the US-Philippine Society (USPHS), joined the Philippine Disaster Relief and Resilience Foundation (PDRF) to establish a medical and education facility for Muslim children displaced in the 2017 Siege of Marawi on the island of Mindanao.

Zf840. A beautifully carved 19th century Santos of Saint Javier, or Saint Francis Xavier, known for bringing the Catholic faith to the Malay Archipelago, India, and Japan, in the early 16th century. From the Philippine Island of Panay. This is the same island on which a heroic American sailor, Telesforo Trinidad, was born. Devine providence? (Writer’s collection.)

A final “Tevelson Grant” of $140,000 will join and support Filipinos with a life at sea. The Philippines, a 7,000-island seafaring nation, also ranks third in the world in natural disasters. There are over 300,000 Filipino mariners serving around the world on commercial ships flagged by many nations. The nation’s maritime academy is one of distinction. From three to four months each year mariners return home to be with their families. An American charity and several Philippine non-profit entities created “Project Rise”, to organize these talented bi-lingual and technically trained skilled mariners and capitalize on their time away from the sea and bring them into a system to help their communities prepare for natural calamities. That system will provide tools and training in disaster preparedness and recovery, especially in hardship prone areas, such as coastal communities subject to typhon.

With our nation’s remarkable history with the Philippines, and thousands

of Filipinos having served in our U.S. Navy, it may be surprising to learn that there has never been a ship named to honor that service. There have been ships named for famous maritime battles in the Philippine islands, and in 1919 the USS Rizal (DD174) was commissioned and named for the Philippine hero, Jose Rizal. The ship was a Philippine donation by the legislature of the American-Colonial Insular Government to serve in World War One. It never did. For the next decade it remained in Asia with its predominately Philippine crew operating out of Manila and Olongapo, converted to a mine layer, and decommissioned in 1931.

Zf841. Telesforo Trinidad was born on the island of Panay, entered the U.S. Navy Insular Force in 1910, and served through two world wars retiring in 1945. The USS San Diego (ACR-6) also served as command ship of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

Last year American veterans, community and other leaders, came together to form the “USS Telesforo Trinidad Campaign”, or “USSTTC”. Telesforo Trinidad was a Second-Class Fireman who in 1915 on board the USS San Diego (ACR-6), an armored cruiser, following a boiler disaster, saved many of his fellow sailors. Nine perished. He received the Medal of Honor (MOH) for his courage and heroism and remains the only Filipino, and Asian American, in the U.S. Navy who has received this recognition. It has been recommended more than once by Navy historians that his heroism be recognized by the Secretary of the Navy in naming a ship in his honor. Not unlike the recent naming of a nuclear aircraft carrier for a heroic African-American, naming a surface combatant USS Telesforo Trinidad would honor not just one Sailor, but thousands who have served with distinction and valor in the United States Navy. It is a mystery why it has not happened before. I am confident it will happen.

Tragically this Spring, events concerning hate groups targeting Americans of Asian heritage began to appear in the news. Philippine-Americans were not exempt. With May having been Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, many national leaders came forth to denounce the absurdity and sickness associated with treating any human on a basis other than understanding, tolerance, and respect. Both the Chief of Naval Operations and Secretary of the Navy made their voices heard.

Filipinos becoming American Sailors enriched our ability to serve. It was my experience, and trust yours as well. It is a legacy that must be honored, a history that must be told.

Zf842

On 19 May 2022, Secretary of the Navy, the Honorable Carlos Del Toro, named an Arleigh Burke class destroyer, the USS Telesforo Trinidad (DDG 139).

Dan McKinnon retired from the U.S. Navy in 1991 as a Rear Admiral and Commander, Naval Supply Systems Command and 36th Chief of Supply Corps. For several years he served as President and CEO of “NISH Providing Training and Employment for People with Severe Disabilities”. Dan joined Retired Navy Captain Dennis Wright as his vice-chair in the successful campaign to change law compelling the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) to assume reasonability for the abandoned American military cemetery at the former Clark Air Force Base. He and retired Naval aviator Captain Brian Buzzell co-founded the Subic Bay Alumni Foundation to sponsor U.S. military tourism to the Philippines, and raise money for typhoon disaster relief and the Olongapo City Hospital. Dan is an Honorary Citizen of Olongapo and an Honorary Son of Balangiga. Dan, Dennis, and Brian were recognized by a Philippine Senate resolution for leadership in returning Philippine icons to their church, the “Bells of Balangiga”. Dan is President of Project Handclasp Foundation sponsoring humanitarian projects in the Philippines. Themckinnons@aol.com

Copywrite 2021